Ukraine-Russia: The risks and rewards of Western escalation

The West can certainly do more to help Ukraine win its war against Russia. But escalation against a nuclear power carries immense risks.

It has now been ten days since the start of the Russian-Ukrainian War and contrary to initial expectations (though not to yours truly who called Russia’s defeat on day two and explained it here), Russia remains no closer to victory than on day one. Nevertheless, the situation faced by Ukrainian forces is still a difficult one, facing considerable inferiority in men and material and an inability to replace losses without foreign assistance from NATO. This situation has called for desperate pleas from the Ukrainian government for NATO to step up its game and involve itself directly in the conflict, such as by setting no-fly-zones. While many Westerners feel that NATO should do everything possible to avoid Ukraine losing the war and possibly losing its very existence, there are risks of turning a regional war into a much wider conflict involving the world’s two biggest nuclear powers.

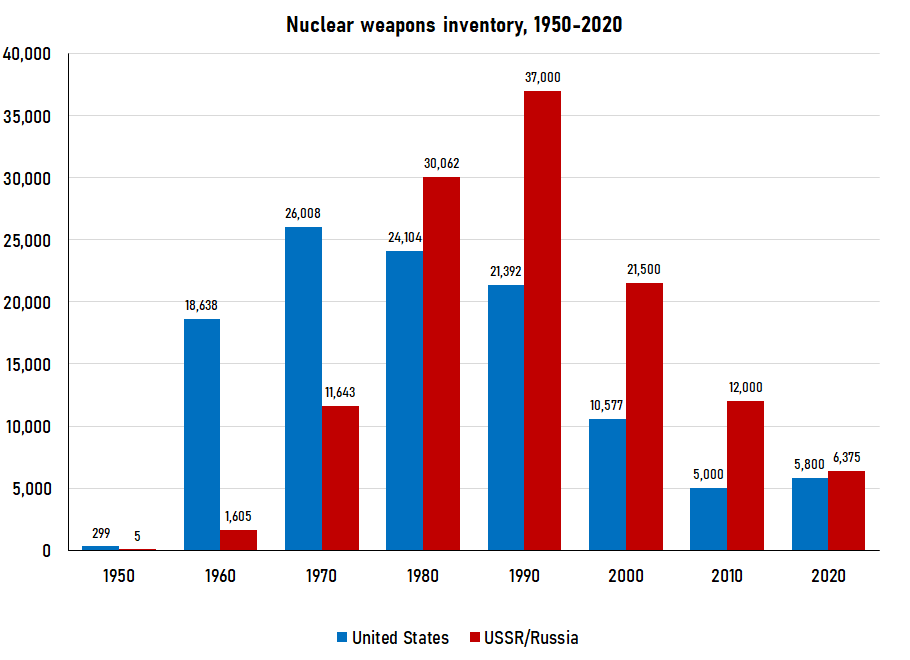

Are these risks justified? The main risk to NATO’s escalation is that any armed confrontation with Russia could rapidly escalate to a nuclear exchange, which would obviously be the single worst possible outcome for humanity imaginable. As bad as Russia’s military has shown itself at waging conventional war, the fact of the matter is that nuclear warfighting is a relatively straightforward affair: you push a button and ballistic missiles fly out of silos and submarines. Poor quality of Russian weaponry and maintenance lead many people to think that many will miss their targets or be duds. This is colossally naive. Even if only half of Russia’s 6,000 existing warheads detonate in the right place, that still leaves enough for the destruction of every major city in North America and Europe many times over.

It is worth mentioning that a conventional shooting war between NATO and Russia does not necessarily have to lead to a nuclear conflict. On this there is plenty of hyperbole from many commentators - perhaps not coincidentally, the same ones that claimed that a war would not happen in the first place or that it’s ultimately NATO’s fault. But this is usually very amateurish punditry that belies a gross misunderstanding of the process of nuclear escalation and how both sides have come to view the prospects of a nuclear exchange since the 1970s.

Let’s first analyze how nuclear escalation actually works before trying to assess the risk of such a scenario occurring if NATO expands its role in this conflict.

Nuclear warfighting, Cold War style

Throughout the first half of the Cold War, the threat of nuclear was underpinned by two distinct imbalances of power between the two superpowers. On one hand, there was the overwhelming US superiority of the US in terms of the number of warheads and delivery systems (bomber aircraft primarily) relative to the USSR. On the flip side, the USSR enjoyed a similar overwhelming superiority in terms of its conventional forces which was a qualitative advantage in many cases as well; for example, Soviet tanks and armored vehicles were better than Western ones on average until the late 1970s. NATO’s strategy during this time was to pre-empt a Soviet invasion of Europe by the only means it had available to guarantee victory: obliterate Moscow and Leningrad the moment the first Soviet tank platoon crossed into West Germany. This strategy was known as Massive Retaliation and it meant that any hostile action from one side would be met with disproportional force by the other.

From the late 1960s onward, this imbalance changed. Firstly, the USSR narrowed the gap in terms of its nuclear capabilities with the US to the point that it achieved parity by the 1980s. Secondly, the advent of nuclear ballistic submarines around this time gave both sides what is known as “second strike” capability, that is, the ability to have enough of your nuclear delivery systems survive a first strike by the enemy and fire back (remember, bomber bases and missile silos can be nuked but the submarines can be anywhere in the ocean at any time). Thirdly, NATO became ever more confident of being able to defeat the USSR and its Warsaw Pact allies in a conventional war in Europe thanks to technological advances in precision weaponry as well as command and control systems. This was exemplified in the AirLand Battle doctrine and proved itself in the 1991 Gulf War where it shattered the Soviet weapons and doctrine of the Iraqi military which at the time was the world’s fourth largest.

The result of the USSR achieving nuclear parity with the US along with NATO achieving conventional parity with the Warsaw Pact was that it made both sides more willing to keep any war between them as purely conventional. In 1967 NATO replaced Massive Retaliation with a doctrine known as Flexible Response, which intended to meet hostile actions more proportionally. This meant that war would likely begin as a purely conventional affair and escalate according to the opponent’s moves, for example responding with tactical nuclear weapons (which are smaller and used only on battlefield objectives rather than strategic targets like cities) if the other side used them rather than immediately jump to a full-scale nuclear exchange.

Granted, neither of the superpowers went as far as they could. Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev, for example, pledged a “no first use” policy in 1982 which meant that the USSR would only use nukes if the other side used them first. Unfortunately, the US did not respond in turn and Russia would later renege on this policy in 1993. Russian military doctrine currently holds that they reserve the right to use nuclear weapons “in response to the large-scale conventional aggression”.

Can NATO do more?

What NATO is doing right now is supplying the Ukrainian military with critical weaponry like anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs) and surface-to-air missiles (MANPADS). These have proven to be incredibly effective and will be even more so if Russia begins to rely more and more on poorly trained and demoralized troops against battle-hardened Ukrainian defenders fighting for their homeland. Turkish TB2 drones have also been used to spectacular success and there are reports that more have been supplied in recent days. These weapons will continue to underpin what has now been the unquestionable tactical superiority of the Ukrainian army. However, Russia’s material superiority means that a brute force approach could still eventually overwhelm Ukrainian resistance insofar as Putin (and Russian society) is willing to bear with the massive losses that such a strategy could entail.

The first thing NATO could do is, of course, to step up and speed up the transfer of material assistance. The US Congress, for example, is set to debate on a $10 billion package of military, economic, and humanitarian aid which dwarfs the $350 million already provided, most of which has already been distributed to Ukrainian combat units. However, this will still take days if not weeks to arrive which Ukraine will have to do with what it currently has to withstand any renewed Russian offensive. Other NATO countries could also step up their supplies though unlike the US, they are not likely to have that many stocks to spare. The state of these weapons could also be in question: there were complaints that many of the German MANPADS (old Soviet-made Strela missiles from former East German stocks) provided days ago were rusty after years of storage and possibly unusable in combat.

Beyond the continued arming of Ukraine, the possibility of providing Ukraine with combat aircraft has also been mulled. Even though the Russian Air Force has – to the surprise of everyone – failed to achieve air superiority, it is still able to undertake air operations with far more freedom than its adversary and the Ukrainian government has been explicit about the need for aircraft. One proposal would see former Soviet bloc countries like Poland and Slovakia hand over MiG-29 fighters which they continue to operate so that Ukrainian pilots who also fly them could literally jump right into them. This plan was initially shot down, then revived, and then finally shot down again by the US on grounds that it was “not tenable” due to the risk of escalation. Though MiGs are a more significant donation than missiles, I frankly doubt it would alone warrant a Russian response.

Another more radical idea has been to send NATO “volunteer” pilots, complete with aircraft, to be given Ukrainian citizenship and their planes painted with Ukrainian insignia. Russia, in fact, has done this plenty of times in the past most notably during the Korean War where Soviet pilots flew Soviet planes repainted with North Korean insignia. The Russian elite troops that captured the Crimea in 2014, described colloquially as “little green men” by the press, were also deployed without insignia and without official recognition by the Russian government that they were in fact, regular Russian troops, as have many of have fought in the Donbas during the past eight years. As a taste of their own medicine this plan would not be entirely undeserved against a country that constantly resorts to plausible deniability for its actions. But from a practical perspective, there is a considerable logistics problem in sending a mini foreign air force that lacks interoperability with the Ukrainian air force. And from a political one, it would also be a much riskier escalation. NATO forces would be de facto fighting Russian ones and to assume that Russia will not consider this a declaration of war is a very risky gamble.

Finally, there is the even more controversial idea of NATO establishing a no-fly-zone over Ukraine. This would mean any Russian plane flying over Ukraine would risk getting shot down, either by NATO aircraft or possibly by NATO air defense troops deployed inside Ukraine. While this plan has been promoted obsessively by the ghoulish security experts that appear nightly on CNN and MSNBC along with no shortage of other liberal centrist pundits, the fact of the matter is that this would be taken without any question as a declaration of war with Russia. Thankfully, it appears this is an idea that is limited to the fantasy world of the American punditocracy (and the people who watch them) but is not one that will be taken seriously by the US or NATO which recently categorically rejected it.

Would war with Russia necessarily go nuclear?

They answer, quite simply put, is that only Russia knows. However, this is far from a given considering how many pundits (mainly on the left) have made it seem like anything more than a sneeze from NATO is going to be met with thousands of Russian ICBMs flying off from their silos. This is beyond preposterous and belies an incredibly amateurish view of the risks involved in such a brash move as well as the safeguards and doctrines established by both sides for decades, including periods when the risk of such a scenario were infinitely greater.

However, to believe that Russia would behave pragmatically also belies the reality that Putin shows evident signs of psychological instability, an unwillingness to admit defeat, and more control over the Russian apparatus of state (including its nuclear chain of command) than any Soviet premier could have dreamed of. It is unclear whether the safeguards that existed during the Soviet era remain in place. Putin certainly does not have a “red button”, as is often caricatured, that he himself can press to launch a nuclear attack. But if we were openly wondering whether the US military could have stopped Donald Trump from starting a nuclear war on a whim, we have every reason to ask ourselves the same question with Putin. We were right to warn of the risks of escalation when Trump ordered the assassination of Iranian general Qassem Soleimani, and we were lucky that Iran showed restraint. But there was no guarantee of this outcome, nor is there with a similar provocation with a nuclear power led by an unstable megalomaniac.

The imbalance of power that now exists between NATO and Russia is also a reason why the risk of a nuclear exchange is more likely rather than less. Russia’s embarrassing performance on the battlefield suggests it would fare badly against a mid-tier NATO country like Turkey, to say nothing of NATO as a whole with the US involved. During a series of 30 separate wargames between Russia and NATO organized by the RAND Corporation during 2014-15, Russia won all of them, reaching the three Baltic capitals in 36-60 hours. In retrospective this now sounds laughable, and is a testament of how often assessments of military power fail to take into account intangibles such as logistics, training, and morale, all of which have proven to be Russia’s Achilles’ Heel. Putin is now well aware of this, and there seems little reason why he would lead his armed forces into what would certainly be an even quicker slaughter against NATO. That means if he has to fight, he might well start off with the nuclear option just like NATO would have done in the same circumstances of conventional inferiority in the 1950s and 1960s.

Are the risks worth it?

In the end, leftists may be certainly hyperbolizing the risks of a nuclear exchange to the same degree that the centrists are downplaying them. But the risk needs to be assessed relative to the reward and, especially, whether a similar reward can be achieved without that risk. And the answer is: there are other options. By far the best weapon the West has in its arsenal are not F-16 fighter sweeps over Kyiv and Kharkiv, whether these be NATO pilots or volunteers (wink, wink). The best weapon are sanctions which so far have left some key Russian vulnerabilities untouched, such as the millions of barrels of Russian oil imports that the US has not yet blocked or the billions of pounds of Russian assets funneled into London properties by dodgy shell companies. Ideally these sanctions should be kept in place not only until a cease-fire is signed but until the last Russian soldier leaves Ukraine, including the Donbas. Maybe even Crimea too. Make the loss hurt.

And it is clear that these moves are hurting, in light of numerous Russian oligarchs now pronouncing themselves against the war. Putin is not one to wince at the fact that ten thousand of his troops may have been killed in combat in barely ten days. But he will begin to feel the pressure if his grip on power begins slipping. Russia is, above everything else, a mafia state, and mafias know very well when their bosses have outlived their purpose to the organization. Of course, nothing guarantees that the much desired ‘palace coup’ scenario will play out in reality (in fact Putin’s grip on power is stronger than may pundits think). But it’s hard to imagine that a collapsed Russian economy will sustain the war effort for more than a few weeks, or sustain public opinion amid the hardship that it could bring about.

Most recently, Putin has warned that the sanctions are “akin to a declaration of war”. In that case, what is he waiting for? The answer, of course is that he will do nothing. But even if this bluff is called, the West can’t get too gung-ho about its options. Ukraine’s victory can be made possible without resorting to no-fly-zones or volunteer pilots. Unless Putin resorts to some form of dramatic escalation himself like tactical nukes or genocide, let’s leave the riskier options off the table.

UPDATE: This piece has been updated twice in light of changes in the status of the MiG deal after it was initially published.

Did you like this article? Follow me on Twitter at @raguileramx and on YouTube at ProgressumTV. You might also like my book, The Glass-Half Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century (Repeater Books, 2020). My security-related work has appeared in The Military Balance, Armed Conflict Survey, and Strategic Survey from the International Institute of Strategic Studies.