The left is getting the Russia-Ukraine conflict horribly wrong

Its knee-jerk support of Russia violates the normative arguments that we need for an international system based on non-intervention

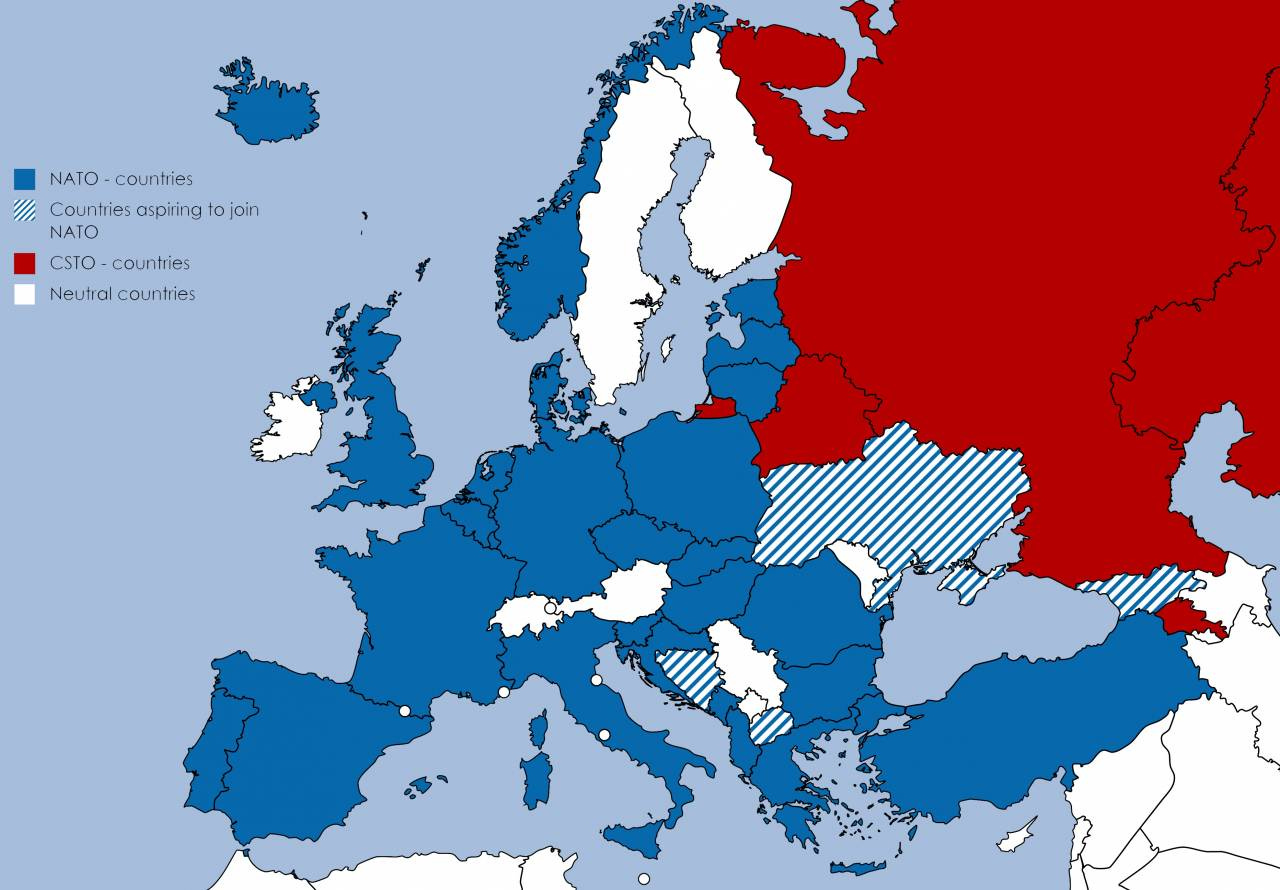

What should the leftist position on the Russia-Ukraine conflict be? I pose this question because ever since this conflict exploded in 2014, leftists have been torn between two sides which have fundamentally imperialist objectives. On one hand there is the NATO, which since 1999 has expanded into Eastern Europe and even into some former Soviet republics (the Baltics), raising the specter of a hostile West on Russia’s doorstep yet again. Russians need no reminder of the suffering and death inflicted against their country during the French and German invasions in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as the lesser known (in the West at least) intervention by multinational armies – including the US – during the Russian Civil War.

On the other hand, there is the undeniable reality that Russia under Vladimir Putin has invaded two of its neighbors, Georgia and Ukraine, the latter which has included the biggest land grab so far in the 21st century (Crimea). Russia also maintains a destabilizing presence in others by arming and supporting separatist movements, and has also intervened abroad in Syria killing over twice as many civilians in the process than the US-led coalition. A friendly neighbor it is not, and it has made it clear that any country in its sphere of influence will face consequences (destabilization at best, full-blown invasion at worst) if it decides to cozy up with the West.

It is understandable that many leftists see US and Western imperialism rather than Russian aggression against its neighbor as the bigger global threat, and are consequently tempted to side with what is presumably the lesser evil. But attempting to justify Russia’s actions against Ukraine open up major argumentative and moral inconsistencies. Should we support a country’s efforts at subjugating another only because enhancing its power is perceived as weakening the West? Should we let Russia get away with actions we would categorically condemn if the US and the West were doing it? Is imperialism exclusive to the West?

The answer to me is clear: no. In this essay I will explain why the most widely espoused leftist justifications for supporting Russia’s actions against Ukraine fall into an argumentative is-ought trap. One that renders any normative view of international relations irrelevant. But before explaining, a little backdrop on the nature of this conflict is warranted to understand why these arguments don’t stand.

The motivation game

For Russia, the motivation is simple: maintain a sphere of influence to serve as a buffer between itself and the West. Currently, this buffer is possibly the weakest that has existed since 1914, when Russia bordered two hostile European empires (Germany and Austria-Hungary). Russia today has borders with four different NATO countries on its western flank; five if you include the Kaliningrad enclave which borders Poland as well. But more problematic is Ukraine, a country larger than any in Western Europe and with a population nearly the size of Spain’s. Losing Ukraine to NATO would therefore represent possibly the biggest foreign policy humiliation that the Putin government could be subjected to. An intolerable scenario.

The US motivation is less straightforward. It is obvious that in this zero-sum global power game, any impediment to Russia’s geopolitical ambitions is a win for the US, just as the reverse is equally true. However, this has to be ideally achieved without provoking a war with Russia, with the US has no appetite to fight (nor does Russia) and which could have devastating consequences if it were to escalate beyond the use of conventional weapons (which I also suspect is to the benefit of neither side). Indeed, provoking Russia to invade Ukraine would serve numerous US interests, hence the impetus for brinkmanship: it would open the door for the US to expand security arrangements in the region to “contain Russian influence”, and to ramp up military spending in what will be argued will be an increasingly hostile geopolitical environment. In short, the US probably does want Russia to invade, and hope to reap the strategic and financial benefits of a war (especially one in which Russia fares poorly) without actually being involved in the fighting.

The motivation of other NATO members is even less clear, and most will probably be content with letting the US call the shots. Aside from the US, there is no NATO state that currently has the military capability to fight a shooting war against Russia. So paltry is the state of European militaries that even the ostensibly French-led Libya intervention in 2011 was only made possible by the US “leading from behind”. Even when the US is included, forces stationed within operational distance to Russia (such as the battalion-sized Enhanced Forward Presence battlegroups in the Baltics and Poland) would have negligible impact on any land war where more than 100,000 troops are arrayed against each other on each side.

The normative argument

The leftist position on international relations should be an obvious one: a world in which there are no spheres of influences, no backyards (or as Biden now calls Latin America, front yards), and where the sovereignty and self-determination of peoples is respected. It should also be a world in which states are allowed to set their own collective security arrangements. We can argue endlessly over whether NATO needs to exist (it probably didn’t after the USSR collapsed though Putin’s Russia has now given the alliance renewed validity) or whether it needs any more members. What we can’t be arguing is over whether any country has the right to join it. In fact, one of the main treaties signed in the post-Cold War years, the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, specifically states the following principle:

Respect for sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of all states and their inherent right to choose the means to ensure their own security, the inviolability of borders and peoples' right of self-determination as enshrined in the Helsinki Final Act and other OSCE documents.

Knowing this, it becomes clear that opposing NATO expansion into Ukraine puts any leftist into the difficult argumentative territory of tacitly accepting a stronger power’s non-existent right to a sphere of influence, one that is imposed by force if necessary. Because if Ukraine is to be denied such a membership, it is only to satiate a Russian demand that violates Ukraine’s sovereign right to establish its collective security arrangements. You can’t have both any more than you can square a circle, and you can’t make exceptions to sovereignty just because your sympathies lie with one side (for most leftists, that will impulsively be the anti-US side).

The is-ought problem in geopolitics

In the face of this argumentative dilemma, many leftists have attempted to justify this exemption by falling into an is-ought trap. As readers may already know, the is-ought problem was conceived by Scottish philosopher David Hume who pointed out that it was impossible to derive an ought (a normative statement) from an is (a positive statement). The is-ought problem is manifested by many leftists claiming that Russia deserves its sphere of influence in Ukraine (an ought) on the basis that the US also has its own spheres of influences around the world (an is).

This line of argument is highly problematic. In a January 24th video, the popular leftist YouTube pundit Kyle Kulniski argued that that the US opposed the Soviet Union installing nuclear missiles in Cuba (a historical is) as proof of why the US now needed to respect Russia’s right to a NATO-free Ukraine (an ought). But the fact is that the US had no right in 1961 opposing Soviet missiles in Cuba, all the more considering that the US had its own nuclear weapons in Turkey which had a border with the USSR. The US’s right to avoid a Soviet nuclear presence in its backyard was upheld only because of its naval and nuclear superiority viz-a-viz the USSR during the early sixties, which prompted the Soviets to stand down and avoid conflict (although they did manage to extract a few less-publicized concessions).

In the same video, Kulinski also argued that this would be akin to Mexico allying with China or Russia if it felt threatened by the US. Again, the is in this scenario is the knowledge that the US would undoubtedly do everything in its power (including attacking Mexico) to prevent it, even if this would violate Mexico’s right to establish whatever alliances it felt necessary to protect its sovereignty. After all, it’s not like the US hasn’t already lived up to these threats in the past.

Misunderstanding Mearsheimer

In support of these arguments, various leftists such as Current Affairs editor Nathan J. Robinson have also quoted a seminal 2014 article written by John Mearsheimer, an international relations expert whose work I am quite familiar with. In that article, titled “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault”, Mearsheimer argues that NATO’s encroachment of Russia through its post-Cold War expansion triggered Russia’s violent response against neighboring countries appearing to gravitate towards NATO’s orbit, namely Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine after the Euromaidan protests in 2014 both of which were invaded. Mearsheimer writes:

The United States and its European allies share most of the responsibility for the crisis. The taproot of the trouble is NATO enlargement, the central element of a larger strategy to move Ukraine out of Russia’s orbit and integrate it into the West. At the same time, the EU’s expansion eastward and the West’s backing of the pro-democracy movement in Ukraine–beginning with the Orange Revolution in 2004–were critical elements, too.

Mearsheimer’s argument seems like music to leftist ears. Except most leftists have probably not read Mearsheimer enough to understand what intellectual background he is coming from. Mearsheimer is a proponent of what is known as “offensive realism”, a school of thought in international relations which establishes that that “states are disposed to competition and conflict because they are self-interested, power maximizing, and fearful of other states”. If you have played the strategy game Sid Meier’s Civilization (as yours truly has for thousands of hours), you’ll find some pretty strong parallels between the game and reality. Offensive realism sees the world as fundamentally anarchic, with only lip service paid by powerful states to the “rule-based international order” that liberal statesmen wax lyrical about. The title of Mearsheimer’s latest book, The Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities, pretty much sums up his position on the matter.

The problem with leftists taking Mearsheimer to heart is that Mearsheimer is correctly arguing through an is-is perspective, not an is-ought. In fact, offensive realism is by definition only a descriptive theory of international relations, not a prescriptive one. Mearsheimer isn’t arguing that Russia’s right to a sphere of influence exists for the greater good of countering US imperialism but simply because Russia is powerful enough to have one. And therefore, that NATO’s encroachment is a dangerous flirtation with conflict with a nuclear state.

Mearsheimer’s disdain for normative arguments is clear towards the end of the article, which I presume most leftists quoting him didn’t get to (emphasis mine):

One also hears the claim that Ukraine has the right to determine whom it wants to ally with and the Russians have no right to prevent Kiev from joining the West. This is a dangerous way for Ukraine to think about its foreign policy choices. The sad truth is that might often makes right when great-power politics are at play. Abstract rights such as self-determination are largely meaningless when powerful states get into brawls with weaker states. Did Cuba have the right to form a military alliance with the Soviet Union during the Cold War? The United States certainly did not think so, and the Russians think the same way about Ukraine joining the West. It is in Ukraine’s interest to understand these facts of life and tread carefully when dealing with its more powerful neighbor.

It would be absolutely preposterous for any leftist to argue along these exact lines in a situation in which the US or NATO (or another US ally like Israel) was the aggressor, rather than Russia. Embracing the Mearsheimer argument essentially disarms any normative leftist view on international relations to the extent that there shouldn’t even be any. We should simply let the world be.

We can’t let it be

Except we shouldn’t. Any desire for an end to Western imperialism cannot place Ukraine and its people on a sacrificial altar to a hypothetical greater good that may be no closer to materializing if Russia gets its way. It is disheartening to see leftist takes suggesting that Ukraine is not a real country as Kulinski implied, or that its sovereignty deserves to be violated merely because of the NATO support it has received (does Russian-puppet Belarus deserve a NATO invasion?). While an obnoxious subset of leftists, namely the Tankie/Marxist-Leninist cohort, have appeared disturbingly gleeful at the prospect of stronger countries crushing the weak (insofar as the weak happen to be US or Western-supported), it is unfortunate to hear toned down but substantively similar arguments deployed by saner leftists. Alas, ever since I first began engaging with the anti-war community in the early 2000s, I have always felt that foreign policy is the one issue where leftists tend most to lose their grip on argumentative consistency, if not reality altogether.

As much as we may think that US and Western imperialism is one of the most malignant forces afflicting humanity today, the fact of the matter is that Russia is the undisputable primary aggressor in its conflict with Ukraine. Period. Full stop. We can argue, like Mearsheimer does, that it is in the interests of peace that the US and NATO recognize their historical role in helping gestate this conflict and that their brinkmanship makes war more likely, not less.

But we cannot argue this from a moral perspective. If we accept that no state has the right to impose its will on another, we cannot let Russia be an exception to how we as leftists think international relations should work.

Did you like this article? Follow me on Twitter at @raguileramx and on YouTube at ProgressumTV. You might also like my book, The Glass-Half Empty: Debunking the Myth of Progress in the Twenty-First Century (Repeater Books, 2020).